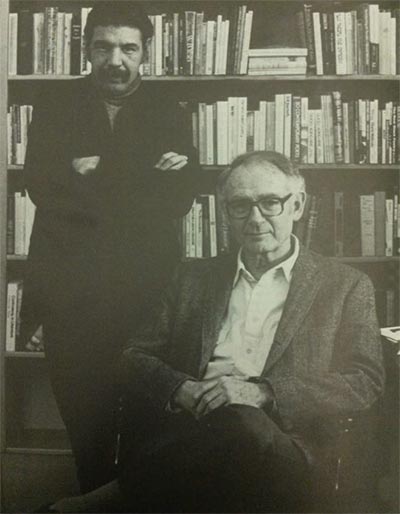

In the fall of 1967 there was no creative writing major at Knox College, but there were two professors dedicated to helping students who wanted to write. Sam Moon, who had been at Knox since 1953, was tall and thin and radiated benign integrity. Robin Metz was an intense young man with thick dark hair, thick dark mustache, all forward motion, just arrived at Knox from Princeton and the Iowa Writers Workshop. He radiated integrity too, of a more potentially confrontational nature.

I was a new arrival as well, a freshman who thought he might want to write for actors but had no idea how to go about it. Robin wasn't my teacher then; he worked with the fiction and poetry writers, and I was one of Sam Moon's two Beginning Playwriting students. (The other, Mary Maddox '71, would later become a novelist.) But word got out quickly on the student grapevine that Robin was (1) sharp and (2) cool, in an exhilaratingly intense way.

In a climate becoming increasingly volatile, politically, racially, sexually, and culturally, he encouraged—and expected—students who thought they were committed to truth to prove it in their writing, to write with emotional honesty. He was an academic iconoclast in an incendiary time. He was political. He proselytized for writers. He held workshops outdoors. He made you work. He made you want to work. He brought with him a double-edged commitment, to writing and the students who pursued it.

I can testify that the unforced aura of honesty he shared with Sam Moon provided, for a young man whose own character was half-formed, a much-needed something to shoot for. Students sometimes have a penchant for spiritual hero worship, but the two professors showed no particular desire to be gurus—Sam didn't want Moonies, or Robin Hoods. They did, however, want to elicit the best we had in us; they met us face-to-face and found out about each of us, acknowledging the different places we came from.

I got to know Robin, and I eventually attended one of his workshops inadvertently because it took place in my apartment, which I shared with one of his students. I don't remember a great deal of what my professors said while I was at Knox—that's much more a comment on my focus than on theirs—but I still recall things Robin said that day, about writing and writers, while he sat on our living room floor.

After four years I went away to Chicago and later to California. And over the ensuing decades, Robin remained at Knox, where he taught, wrote, and fought for the cause of the creative writing program with relentless, evangelical fervor, cajoling and sometimes battling with a series of presidents and deans.

Coming from a blue-collar upbringing in Pennsylvania, he had found, at Princeton and Iowa, that writers in academic settings were often treated as second-class citizens. ("In Iowa, the artists were in Quonset huts held over from WWII that weren't air-conditioned or heated, and at Princeton, Philip Roth was one of my teachers there, he never had an office, they didn't even give him an office, he'd won the National Book Award.") It was only in Robin's later years at Iowa, he says, that the writers' workshop "became so famous that the English department wanted it back."

So Robin took it upon himself—first in partnership with Sam Moon, and, after Moon's retirement in 1985, with colleagues such as Ivan Davidson and Robert Hellenga—to build, at Knox, an unprecedented undergraduate creative writing program, that would eventually include workshop courses in fiction, poetry, playwriting, screenwriting, and nonfiction, courses on single authors (including Yeats, Hemingway, Woolf, Beckett, Richard Yates—another Metz mentor and friend—Toni Morrison, Flannery O'Connor, and August Wilson), and student-group odysseys to Dublin, to Cuba, to London, to the earth from which some of that work grew.

As he proposed these increasingly audacious plans, Robin and the Knox administrators weren't always on the same page. His insistence on continued expansion of the department often met resistance or outright refusal. But his persistence, his energy, his conviction that what he was proposing was for Knox's good—how could it be bad, after all, to have the greatest undergraduate writing program in the history of the universe?—wore down and usually overcame that resistance, so that today . . .

It is officially the 50th anniversary of the birth of the Knox creative writing program—a birthday chosen primarily because it coincides with Robin's arrival. In the half-century since, he has nurtured, mentored, and hectored thousands of students, in workshops and one-on-one, encouraging them to do all they're capable of, to find their personal approach to art and life.

The enthusiasm and achievements of the faculty and students have fed each other, to the point that, as Robin points out in the Knox brochure released to help celebrate the half-century milestone, "...currently, Creative Writing is the largest major at Knox... the size of the Creative Writing faculty has grown from two writers in 1967 ... to nine (widely published and awarded) writers today....Small wonder that Poets & Writers magazine (New York) featured Knox (with Oberlin and Sarah Lawrence) as one of the top three undergraduate writing programs in the nation."

Knox student writers have won so many awards, in competitions such as the Nick Adams short fiction contest and in literary magazines such as Catch, that, Robin has said, "if it were for a basketball team, banners would be flying from every building." Of even more importance, both to Robin and Knox students past and present, the department has nourished an inner soil for the development of the creative process which allows them to thrive not only in writing-allied areas after graduation, but in virtually any other career they pursue.

I left Knox in 1971, to become an editor in Chicago and, later, a writer in California, and didn't return except for a couple visits until 2010, when Robin—showing a typically Metzian willingness to gamble on his judgment of an ex-student's capabilities—got permission to bring me back to lead workshops in fiction, playwriting, and screenwriting.

“

Robin has nurtured, mentored, and hectored thousands of students, in workshops and one-on-one, encouraging them to do all they're capable of, to find their personal approach to art and life.

I knew, of course, that in the intervening years Robin had been gone from strength to strength as an eminent Knox professor, and I had read his stunningly powerful book Unbidden Angel, poetry dedicated to his late wife, Liz Jahnke. I knew also that with his present wife, Knox theatre department co-chair Liz Carlin Metz, he had summoned up the extra energy to found and maintain an acclaimed Chicago theatre, Vitalist, which had already presented several critically hailed plays, including his own Anung's First American Christmas.

His c.v. by then included a carpet-sized list of achievements, titles, honors, and awards as both teacher and writer, a few of which included the Rainer Maria Rilke International Poetry Prize for Unbidden Angel, the Dylan Thomas Poetry Prize, the Marshall Frankel American Fiction Prize, and both the untenured and tenured Philip Green Wright prizes for distinguished teaching. Now he was Philip Sidney Post Professor of English and director of the Program in Creative Writing.

About that program: Upon my return to Old Main, I found an English department which had grown to nearly a dozen accomplished writer-teacher-academics, each uniquely qualified for their primary form or forms, each committed, in true Metz (and Knox) tradition, to their students. I was a freshman again—intimidated again, too. Big guns everywhere.

The Gizmo offered a vintage Twilight Zone temporaldislocation effect. It looked much as it had 40-plus years before, as did the students—a few of whom resembled Michael Shain '72, Bruce Hammond '71, and Judee Settipani '71, who had been there with me the first time around. My old student friends weren't there, of course. The Knox people I'd known had all changed and gone.

Except for one, sitting at a small table across from a student, leaning forward.

I couldn't figure it. Not only was Robin Metz still there . . . he hadn't burned out! Firebrands burn out, don't they? The first president and administrators he'd battled on behalf of some imagined creative writing department were gone. So were the second and third presidents and the second and third wave of administrators. Like us, the students of the previous century—we were all puffs of smoke. But Robin Metz was leaning forward to find out what this Knox student had to say for himself.

I couldn't figure it. I had to find out how he did that.

When the 50th anniversary celebration schedule was set up, it included on-campus readings from celebrated writer alumni, plus several trips for Robin, to attend alumni events and reunite with former students in Chicago, San Francisco, New York and other venues. Last December, as these scheduled events were about to begin, he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. He began a grueling first round of chemotherapy shortly thereafter. I assumed, upon hearing of this, that it would prevent his attending the out-of-town anniversary events. Through April, he had made them all.

Also in April, he sat down in my kitchen to reflect on the way his teaching evolved over his years at Knox, and I got a chance to ask him how he went from a firebrand to a kind of eternal flame in his fight for the "creatives." Here are some excerpts from our talk.

Q: You've been referred to as the Dumbledore of the Knox creative writing department....Is that acceptable to you?

A: I actually think of it as flattering because I loved him on the screen-

Q: It's meant to be—

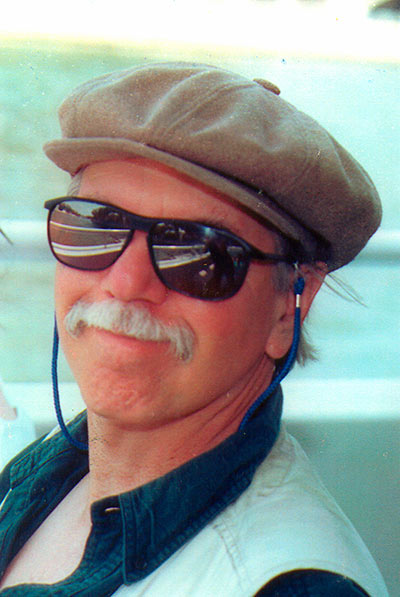

A: For the record, as we speak, I have no hair except the last little fringes of my mustache, which I've decided to let fall out naturally.

Q: That was the one change in you from seeing you in the Gizmo when I was a student, talking to writing students. I came back 40 years later and everything was different-except one thing, and that was you, sitting at a table, talking to a student about their work. And the only change I could see in the 40 years was that the mustache—

A: —was white.

Q: You have such a network of student writers that have built up over the years and now you're seeing some of them on the (50th-anniversary city-visits)—

A: It's been great, it's why I'm doing it, really.... I'm so proud of them and what they've achieved and, in a lot of instances, I don't know the full range of their achievements. I get to hear that, and then I bring it back and tell my current students about it, and, in some ways, I serve as a belief bridge for contemporary students-to believe that actually by doing this study at Knox that it can go somewhere.

Q: I haven't had as much experience in other places as you have, but I did see some other students when I was in California, and it seems to me that Knox students for some reason were much more jacked up about the idea of what they were trying to do than most of the ones I'd seen...

A: I think there is something about the culture of the place, really, and all of us ... are at least partially responsible for having created that.

Q: It's good for peripheral things too. By the time I left Knox I was a really good typist, and I got a job as a temporary typist at Field Newspaper Syndicate, typing columns by Ann Landers and Roger Ebert and that crowd .... Basically I was using tools I got at Knox, not quite in the way that I was working at Knox but still with writing and writers, and I'm sure that happens with hundreds of the students....

A: We have to convey to the students that what we instruct them in is not the creative product—though that's what we seem to say: Write this great short story or play or poem or series of poems, and be so proud and happy of the product, and try to get it published. But what we're really focused on is the creative process. And when you stress that and begin to model your teaching in ways that allow for that, then there's value that's being transferred to the students and the student's way of thinking. Whether or not their product ends up being saleable and establishing them in that career, they get to be the people who, in a whole range of industries, become the creators—

Q: The creative ones there—

A: Yeah, right, and you know there's this whole class of workers now known as the "creatives"—

Q: Oh really?

A: Yeah, it's like the buzzword of American commerce. "The creatives."

Q: "We need more Creatives."

A: Yeah, and they're hired to be the problem-solvers in any range of situations—

Q: And that makes sense.

A: It does because—to use a cliché—"thinking outside the box" is what you do every time you write a poem or a story, you have to work your way through the problems involved. So this whole moral/ethical question, "Are you selling a bill of goods when you're selling someone on the arts because they imagine themselves on the big screen or the New York Times best-seller list," now you can honestly say that what you're conveying to them will be valuable and useful in their careers whether or not they remain directly in the arts.

Q: Is there anything left undone? Is there anything left for you to write? You've been busy. My experience here is that I can't write while I'm teaching, except during breaks.

A: Well, that's something of an issue for me personally in a way. I've written and published a lot but not as much as I want to, and I have such a backlog of stuff that I really want to do, both fiction and poetry... and plays! In particular, I've been dying to do this one play which is actually an adaptation of a lesser-known Hemingway novel, and I just think it'd be so great for the stage—even though I subsequently discovered that there was a perfectly dreadful film once made of it.

Q: Which one is it?

A: Garden of Eden.

Q: All right, I want to ask you something—I was trying to figure out why you didn't burn out.... I had a job at a newspaper syndicate and after 10 years I burned out. I knew everything I had to do there and from then on until I left I was just there. And I came back here, and I saw what you'd built and that you were still as committed to the individual students as ever, nothing had changed. My theory is that it's the students in a way that give it to you—

A: Sure—

“

IN SOME WAYS, I SERVE AS A BELIEF BRIDGE FOR CONTEMPORARY STUDENTS—TO BELIEVE THAT ACTUALLY BY DOING THIS STUDY AT KNOX THAT IT CAN GO SOMEWHERE.

Q: —because of the nature of our work—it's emotional and it's intense, and it's exhausting, but it's also exhilarating, is that—?

A: Even if I was teaching the same literature course every year, I wouldn't teach the same book somehow. I'm always changing because just to do the same thing ... makes you more expert in it and more polished, but in some ways you grow farther and farther from the students, right? So, in our kind of work, in the workshops, you're always beginning at ground zero.

Q: And everyone is a new set of problems—

A: Right, there's no workshop where one was ever like the next, even from one term to the next, even if you had mostly the same people it would still be different. So that's generating....

There was a big boost in my personal life when, in honor of Liz Jahnke, Liz Carlin and I decided to start this (Vitalist) theatre in her memory in Chicago, and it was great for Liz and it was great for me, and it put us in the Chicago world. The collaborative efforts of working in the theatre as opposed to our lonely writer world was exhilarating. And then I started this London course, which we do every two or three years, so there was all that world to learn about in London, and it's such a gorgeous city. So we feel at home in London and New York and Chicago and in the country and here. I'm not a Knox person that hates Galesburg, I just love the whole thing, but it's also true that I've taken it in small doses. I have all these other things to do so when I am here I'm happy for what . . . it's so easy to go to the hardware store! (laughter) I mean to go and buy nails and screws, think in Chicago what it's like if you have to go out, when we're building a set in the theatre, and I'm running all over town trying to find a parking space so I can get 10 bolts!

Q: Well, I hadn't thought of that—that you built out as well as keeping the core.

A: I think that's what kept me fresh, honestly. And then I would bring that stuff back as part of the teaching stuff here.

Q: But now Knox has built out too, in that regard.

A: Well, and once I'd done London I realized—I don't know what it was that made me start single-author courses—

Q: Oh yeah!

A: —maybe it was Virginia Woolf, but I realized that almost no literature programs anywhere (were) getting any depth for particular important authors.

Q: Shakespeare maybe—

A: Shakespeare, and there were courses in Milton and Chaucer, Knox had always had those, but contemporary, twentieth-century writers—our young people first of all hardly knew their names, much less the depth of their work. So if you had a study, just in one person's life and work, you could extrapolate from that to your own life and career, plus other writers, and you would see a dimension to it. So I started this long string of—I don't know, I probably have done 12 or so. Q: Is there anything that strikes you, looking at the way creative writing started and the way it's grown, is there anything you feel left undone, anything you'd change, and what do you feel best about? A: Well....I love it that we've just trounced the other ACM schools (in the Nick Adams short story contest)—

Q: Is there anything that strikes you, looking at the way creative writing started and the way it's grown, is there anything you feel left undone, anything you'd change, and what do you feel best about?

A: Well....I love it that we've just trounced the other ACM schools (in the Nick Adams short story contest)—

Q: Yeah, I love that little chart—(in the 50th anniversary brochure listing Knox's Nick Adams winners compared to other colleges in the ACM).

A: (laughter) And I love the other one, the Catch one too. And partly I think this goes back to the feeling, not at all so much for me personally, but that sort of class thing that I was talking about before, that the arts have been tolerated in so many institutions but they're always the first thing cut whether in high school—they can't put the band together anymore or they don't have any money for theatre—they're always expendable. And I was so determined here to find a place that was vulnerable to the idea that the arts were not expendable, that we could become central to the success of the place. And so I'm proud that we have made a space for the arts here with creative writing. But left undone—and maybe I'll still have time—I feel we are so close to being able to make part of our arts picture, film production, and I feel it's so crucial—and we should be doing animation and stuff like that....

Q: You're still a good teacher, you're still—I keep learning stuff from you, the last few years.

A: You know, what you said before about how we get from the students—it's from our friends, too. I think what actually makes great teaching is the people who are genuinely in conversation with these other people that they're talking to—who are sometimes called students, are sometimes called friends, and sometimes called wives or lovers. We're just wholly engaged with this other person, then we give them our person, then we're getting it back—

Q: —we get something back—

A: —and you go home at 12 o'clock and that's ... exhausting but I never felt tired when I was doing it.

Q: It has to do with keeping it new, and it has to do with the people you're with.

A: And see—here's a big change: I shifted from teaching the product, teaching people to do the product, to showing them it was more important to learn the process. We're thinking, "What is creative writing about? We're teaching the creative process." And I even went and studied all this neuroscience stuff and everything about how creativity is really happening, and I was thrilled to bring that to bear. The other big change that came for me was I realized there's a profound difference between thinking of yourself as a professor and thinking of yourself as a teacher. Because as a professor, you are there to profess, and your first and primary obligation is to the world of your material-to pay honor to the accumulated tradition of this wonderful thing that you are teaching. To be a teacher is actually to take the student, where they are, and to bring them as far as you can toward this wonderful body of knowledge and understanding—but it's about them. When you're professing I would say, "Look, I'm kind of infamous for getting off subject, and if I get an idea ... it's like a white-tailed deer tail just went up, bobbing through the woods, and I'm running helter-skelter after it, and follow as best you can, and I'll see you up ahead on the ridge." I used to actually say that. Now, it's like, "Come along—if we lose sight of the deer we'll walk around this way, are you all with me? We'll catch it coming back the other way!"

English Department Colleagues on Robin Metz

I asked some English department colleagues to provide their own article on Robin in "one or two sentences." While chafing at this preposterous restriction—and in some cases, of necessity, impelled to bend it—they rose to the challenge.

"Robin's vision and his tenacious and unending faith in the arts, in language, in each new generation of writers to immerse themselves in a tradition begun long before they were, to carry forth that tradition, and to make from that tradition something new, are just a small part of what I think of when I think of this man I call one of my dearest friends, still call my mentor, have been proud and humbled to call my colleague for now 19 years. His care, his attention, his commitment and loyalty, his joie de vivre, his deep compassion—all unmatched—have influenced so many of us who now aspire toward and aim to honor him in our own work." — Monica Berlin '95, Associate Director for the Program in Creative Writing and Chair of the Department of English

"His dedication to the students, and the creative writing program, is absolute." — Natania Rosenfeld, Professor of English literature

"Robin's an artist, so he offers creative solutions to problems and, sometimes, creative problems with impossible solutions. That's one reason his students love him, that imaginative challenge he sets for them; it's also the reason he so often has unimaginative administrators hiding under their desks." — Rob Smith, John and Elaine Fellowes Distinguished Professor of English

I first formed a bond with Robin while talking to him from a phone booth in Vietri sui mare, Italy, the summer before 9/11. I wasn't sure where to go after living for a year in paradise, and he made me feel like I belonged at Knox—should return to teach there in the fall. . . . Sometimes I feel like we grew up in the same woods, either side of Cheney Creek. . . . Since that time, I have gotten to know Robin on the grounds of poetry and fatherhood. It is because of a story he once told about one of his children, who remembered talking to him through a closed door, that I keep the door open when I'm at my desk at home. Because of Robin, I believe that writing and parenting are not separate lives. Also, I believe in the near-holiness of interruptions." — Nicholas Regiacorte, Associate Professor of English

"Robin has always served as an inspiration for his colleagues, as well as for his students." — Robert Hellenga, George Appleton Lawrence Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus of English; Distinguished Writer in Residence

"Robin chastised me once when I was his student. I'd tried to condense an entire lifetime into a short story, and it was too massive to constrain within the form. ‘This is the tip of an iceberg,' he said. ‘What's under the water is the size of a damn continent.' So it is with my attempt to summarize his impact on my life and the lives of so many others. He is a continent of a man." — Cyn Fitch '00, Associate Professor of English

"Once, during a particularly heated English department meeting, I lost my head and called Robin a two-pronged name ending in ‘ucker.' Even though he kept right on talking, his meditative glance in my direction acknowledged my frustration (he felt my pain!) and assured me that it would continue for yet a while longer. (I don't mean this to be in any way backhanded. I love Robin.)" — Barbara Tannert-Smith, Associate Professor of English

"Robin Metz is one of the most empathic people I've ever met, and certainly the most honest, brutally so at times. He also forever changed the course of my life. I published a short story in Catch my freshman year, and after reading it, he tracked me down. He sat down with me on the Gizmo patio and told me I needed to be a writer. And that's exactly what I did. I went from being a very troubled kid to a focused, purposeful one, and that is all due to Robin....He is also one of my favorite people in the world." — Katya Reno '99, Visiting Assistant Professor

Life with Robin is a magical roller coaster. Or maybe a tilt-a-whirl. No, wait. Life with Robin is both. Definitely both. I wouldn't have it any other way." — Liz Carlin Metz, Smith V. Brand Distinguished Professor of Theatre