How student initiatives change the College

By Peter Bailley '74

When students take the initiative, it's not always pretty. If you had visited the Eco House some four years ago, you would have been greeted by several big plastic bins, filled with damp dirt and lots of big red worms. Some visitors said the bins smelled bad. But the students were committed to reducing food waste through composting. An earlier generation of students confronted a different mess on campus. In the spring of 1950, The Knox Student blasted a campus culture of "cheating on quizzes, themes, achievement tests, final examinations." The student response in the 1950s was another initiative, the Honor system. Knox student initiatives have not always succeeded and not always pleased everyone, but many have transformed the campus, the curriculum, and the core of the College itself.

The first student initiative of record, in 1851, was motivated by a now-familiar cause: Knox students asserting their role in everyday campus life. Students wanted to celebrate Christmas; the College did not. Knox's first two presidents, Hiram Kellogg and Jonathan Blanchard, deliberately scheduled classes on Christmas Day, based on the belief that the celebration of December 25 was pagan rather than biblical in origin.

"On December 24, 1851, [students] unsuccessfully attempted to stop classes from taking place the next morning by hiding the bell, removing keys to the recitation rooms, and locking the doors after having sealed the window latches," wrote Owen Muelder '63, in the anthology Christmas in Illinois. Outraged faculty convened, but the "10 students called before the investigating committee ... must have agreed not to implicate anyone.... Therefore school officials were left with only denials." Muelder wrote that Knox "finally relented" after Blanchard left, enacting a two-day Christmas break in 1859.

Today largely regulated by a non-student establishment -- including conferences and the NCAA -- athletics began as a student initiative, according to Hermann Muelder '27 in Missionaries and Muckrakers. The first public mention of organized sports was in 1857, Muelder wrote, when two student clubs, the literary societies Adelphi and Gnothautii, debated playing football against each other. Ultimately, the societies decided not to, as a commentary in the Gnothautii magazine criticized athletics as "useless and senseless games" of the "heathen Greeks." Rather, the student author argued, "the educated man [should] resort to useful bodily labor."

The students who wanted to play had to form their own clubs -- baseball in 1867 and football in 1872. Years of informal competition preceded these sports gaining true intercollegiate status -- baseball in 1880, football in 1885 -- which ultimately led to the formation of athletic conferences. In recent years, student founded teams in lacrosse, water polo, and Ultimate (a.k.a. Ultimate Frisbee) have made strong showings at the intercollegiate club level. Two modern clubs that made the jump to conference status were women's soccer in 1986 and women's golf in 1995.

Athletic events that required facilities, not just fields, began in 1866 with women's gymnastics, what would today be called calisthenics, followed by men's gymnastics in 1869. While women had their own exercise space in the Female Seminary -- a.k.a. Whiting Hall -- men did not. Knox's first dedicated sports venue was a student initiative: "A gymnasium for the College men was finally built by the students themselves" in 1876 at a cost of about $1,500, Muelder wrote. The next gymnasium, now the Auxiliary Gymnasium, would be a larger project than students could manage. It was completed in 1908 at a cost of $30,000 -- the equivalent of more than $700,000 today. Today 60 percent of Knox students are involved in athletic activity at various levels, and their input is a key element in the planning, financing, and construction of multi-million-dollar athletic facilities.

Athletic events that required facilities, not just fields, began in 1866 with women's gymnastics, what would today be called calisthenics, followed by men's gymnastics in 1869. While women had their own exercise space in the Female Seminary -- a.k.a. Whiting Hall -- men did not. Knox's first dedicated sports venue was a student initiative: "A gymnasium for the College men was finally built by the students themselves" in 1876 at a cost of about $1,500, Muelder wrote. The next gymnasium, now the Auxiliary Gymnasium, would be a larger project than students could manage. It was completed in 1908 at a cost of $30,000 -- the equivalent of more than $700,000 today. Today 60 percent of Knox students are involved in athletic activity at various levels, and their input is a key element in the planning, financing, and construction of multi-million-dollar athletic facilities.

Despite the prominence of college sports today, athletic contests began, at least at Knox, as a sideshow to oratorical competitions arranged by the student literary societies Adelphi and Gnothautii. In the 1880s and 1890s, intercollegiate "athletic contests were staged in connection with most of these bouts of speaking, but they were only the preliminaries ... athletes were primarily a cheering section" for the debate teams, wrote Wade Arnold '28 in College Hero -- Old Style.

Despite the prominence of college sports today, athletic contests began, at least at Knox, as a sideshow to oratorical competitions arranged by the student literary societies Adelphi and Gnothautii. In the 1880s and 1890s, intercollegiate "athletic contests were staged in connection with most of these bouts of speaking, but they were only the preliminaries ... athletes were primarily a cheering section" for the debate teams, wrote Wade Arnold '28 in College Hero -- Old Style.

Oratory was more than entertainment or celebration. Hermann Muelder wrote that the literary societies transformed "the intellectual as well as the social character of the College in ways not anticipated by the founders and sometimes not approved of by those who succeeded the founders in formal authority." The 19th-century classroom experience consisted of lecture and recitation. Discussion as we know it -- as we take for granted -- had no place in the formal curriculum. But it flourished in Adelphi (Greek for "brothers") and Gnothautii ("know thyself") founded by men in the 1840s, LMI (Ladies Mutual Improvement) by women in 1861, and, finally, a society for the Knox Academy, i.e. high school students, in 1864.

Students debated, Muelder wrote, "what they regarded as the critical issues of the day ... capital punishment, free homesteads for settlers, the need for a new translation of the Bible, the controverted justice of the Mexican War, the Mormons, tax-supported commons schools ... were the races intellectually equal? Could one vote for a slaveholder for office without incurring guilt?"

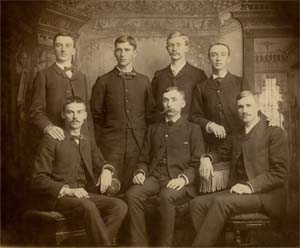

Victories by Knox's star orators were occasions for all-night celebrations, on campus and in the community. After John Huston Finley, an 1889 Knox graduate and later president of the College, won an 1887 oratorical competition -- in which he lionized the abolitionist militant and martyr John Brown -- the bell in Old Main was rung until it shattered. In his autobiography Always the Young Strangers Carl Sandburg described boisterous revelry that followed Otto Harbach's victory in an intercollegiate competition in Galesburg in 1895 (Finley and Harbach pictured at right).

Victories by Knox's star orators were occasions for all-night celebrations, on campus and in the community. After John Huston Finley, an 1889 Knox graduate and later president of the College, won an 1887 oratorical competition -- in which he lionized the abolitionist militant and martyr John Brown -- the bell in Old Main was rung until it shattered. In his autobiography Always the Young Strangers Carl Sandburg described boisterous revelry that followed Otto Harbach's victory in an intercollegiate competition in Galesburg in 1895 (Finley and Harbach pictured at right).

You could hear gunshots ... cannon ... fireworks ... railroad-engine whistles tooted. City and farm boys rampaged around bonfires on the campus and in the streets. Glee clubs sang and wild yells came on the air from before midnight till past daybreak. You could hear voices getting hoarse from crying "Hurrah for Knox!" followed by "Hurrah for Harbach!" ... a wild mob followed the students who hauled Harbach to the campus on their shoulders.

The societies also explored theatre decades before it became part of the formal curriculum. With its pagan origins and portrayal of scandalous behavior on stage, theatre was held in low regard by Knox's founders. Muelder wrote that students were the first to realize its potential:

Occasionally [through the 1840s] the literary societies presented a discourse in the form of a [student-written, student-directed] "conference" on some historical, literary, or political theme.... The "conference" presented at the Commencement in 1846 was only in the most rudimentary sense a dramatic piece, each of the "characters" speaking from the point of view of one of the professions, but it marks the beginning of a rapid evolution in dramatic presentation.... In 1848 a "mechanic" was hired to build a "stage" [and] terms such as "scene" and "dramatis personae" were used.... In 1853, the performance was frankly described as a "play in Two Acts."

The literary societies were founded in the attics of the East Bricks and West Bricks residence halls. By the late 1800s, the societies had outgrown these modest quarters and competed to raise renovation funds. "The rooms which we now occupy are universally condemned and unfit for their purpose ... mere garrets, too low for speaking, too small even for our ordinary proceedings," wrote leaders of Adelphi and Gnothautii in a joint letter to the Board of Trustees. "We feel that we have the right to ask you to make an effort to furnish us with Halls better suited to the wants and character of the societies."

The two societies received dramatic new spaces in the center of campus, with the construction of Alumni Hall in 1890. Each student group received a wing, Muelder wrote -- "a spacious meeting hall [on the second floor] with stage and dressing rooms, a reading room and a library.... The first floor would have a large parlor that students ‘might use between recitations for study or other purposes as may be desirable'." The core of the building was named after the ones who paid for it, Knox alumni, but the names of two student groups, Adelphi and Gnothautii, are carved in stone, front and back, above their respective east and west wing doors.

The two societies received dramatic new spaces in the center of campus, with the construction of Alumni Hall in 1890. Each student group received a wing, Muelder wrote -- "a spacious meeting hall [on the second floor] with stage and dressing rooms, a reading room and a library.... The first floor would have a large parlor that students ‘might use between recitations for study or other purposes as may be desirable'." The core of the building was named after the ones who paid for it, Knox alumni, but the names of two student groups, Adelphi and Gnothautii, are carved in stone, front and back, above their respective east and west wing doors.

Along with initiative, the literary societies had independence unheard of in the modern era. The societies brought in their own speakers, but they also raised their own funds. The founding of Adelphi in 1846 included a formal charter issued by the State of Illinois -- as if today's student clubs formed their own nonprofit corporations. In 1876, Gnothautii received a gift of $500 from Gen. David S. Colton, Class of 1853, to endow the Colton Prize in Public Speaking, the College's oldest student award. Colton, who died in 1878, was active in real estate speculation, thus it's no surprise that in 1905 Gnothautii invested the $500 endowment in a bond issued by Canyon Canal Company of Idaho. In 1912, the club was informed that Canyon had closed, and Gnothautii was now the proud owner of a $500 municipal bond issued by an irrigation district that had taken over Canyon's debts. It required the College treasurer, bankers, and lawyers, including prominent attorney Philip Sidney Post of the Class of 1887, to untangle the complex transfer -- not the sort of dealings that a student club should be involved in.

With many Knox men serving in the Union Army, enrollment of women buoyed the College through the Civil War. After the war, even as Knox classes were enrolling both men and women, Knox President William S. Curtis in March 1868 attempted to roll back the clock on coeducation, advocating separate classes for the sexes, as well as lower salaries for female faculty.

With many Knox men serving in the Union Army, enrollment of women buoyed the College through the Civil War. After the war, even as Knox classes were enrolling both men and women, Knox President William S. Curtis in March 1868 attempted to roll back the clock on coeducation, advocating separate classes for the sexes, as well as lower salaries for female faculty.

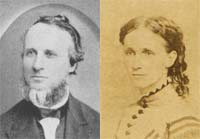

President Curtis's actions, Muelder reported, brought him into conflict with Lydia Howard, principal of the Female Seminary (Curtis and Howard pictured at right):

The president, in a quarrel with the principal over the copy for the next year's catalogue, had seized the manuscript from the lady's hand. Howard and two other women from the Seminary faculty tendered their resignations "in consequence of personal difficulty between the Principal and President Curtis." On the morning of the next day, all of the town was aroused to the knowledge that something excited the Knox students. The bell on the main College building kept ringing.... Students had mounted the roof [and] cut the bell rope. Some of them [fired] old muskets that had been used by the student cadets during the war.

Students then refused to attend class. Their hand-written petition threatened to "have no further connection with the institution until we receive written information from the proper authorities that President Curtis has no further connection with this institution." A student who took part in the protest, James Parks of the Class of 1872, wrote later that it was, in his view, "the first ‘sit-down' strike in history":

When the Chapel bell rang there were only three who went up to services and recitation. We remained on the grass sitting and talking, laughing and singing.... For the afternoon and evening Chapel we did exactly the same thing. We sat on the grass, saw the faculty come and go and also the three students, but the rest of the students stayed on the grass and agreed to continue that until we heard from the Trustees.

The next day, Trustee Charles Lawrence, vice chair of the Board and later chief justice of the Illinois Supreme Court, met with the students to announce that Curtis had resigned. Yet equality was not achieved overnight. Chemistry Professor Albert Hurd, one of Knox's leading 19th century faculty members, admitted in 1906 that "it has taken us 60 years to reach the time when men and women were in reality on equal terms in college life, college studies, and college honors."

In fact, it would take another 60 years beyond Professor Hurd's tenure for women to achieve equality in residential college life. Numerous, detailed rules governed the lives of women on campus -- enforced by the administration, but apparently many drawn up by students themselves. In 1921, the Women's Self-Government Association proclaimed, "Girls may have evening engagements other than concerts, lectures, and recitals with men only on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday night." In the late '40s, the Knox Association of Women Students (KAWS) promulgated "rules to be followed by sun-bathers: No sunbathing on any roofs.... No boys where you are sun-bathing.... Sun-bathe only in the back yards of your respective houses ... as far from the street as possible."

The elimination of hours for women began with seniors in fall 1967. Arguing the next year to extend the policy to juniors, the College Women's Council wrote, "a college education that does not permit [a woman] to make choices and act according to her own judgment, socially as well as intellectually, is an inadequate education." Hours for women officially ended on October 31, 1969.In the 1930s, first-year women had to be inside by 8:30 p.m. Each year of academic standing got you another half-hour of time. An undated mid-20th century survey of schools in the Midwest Conference showed that Knox had overall the earliest hours for women. By 1961, "in light of increasing student demands for social freedom," KAWS opened a discussion of "a great reduction in the number of women's regulations" and began advocating "a policy of open women's dormitories."

Following World War II, "the influx of [GI Bill®] veterans altered the demographics of Knox's student body," wrote Grant Forssberg '10, now a graduate student in history and one of the contributors to the timeline on Knox's 175th anniversary website. College officials lamented the veterans' "habituation" with alcohol and cigarettes. On a political level, Forssberg wrote, some of the veterans "interpreted bigotry on the homefront to be antithetical to what they had fought for in the war."

One of those veterans was Earl I. McGill '47. A Galesburg native and the only African American in his class, McGill entered Knox in 1940, was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1943, then returned to Knox in 1945 to complete his degree in music education. In summer 1946, two young African American married couples were lynched in Georgia by a white mob. One of the victims had recently returned from service in World War II. A few months after the lynching, McGill wrote an article for the campus magazine The Siwasher calling on Knox students to become "leaders [who will] educate the mass which is now spreading terrorism, violence and brutality throughout the land."

One of those veterans was Earl I. McGill '47. A Galesburg native and the only African American in his class, McGill entered Knox in 1940, was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1943, then returned to Knox in 1945 to complete his degree in music education. In summer 1946, two young African American married couples were lynched in Georgia by a white mob. One of the victims had recently returned from service in World War II. A few months after the lynching, McGill wrote an article for the campus magazine The Siwasher calling on Knox students to become "leaders [who will] educate the mass which is now spreading terrorism, violence and brutality throughout the land."

McGill, who would become a career educator in Alton, Illinois, wrote that he didn't expect education to create a utopia, but "at least a harmonious way of life, in which citizens are citizens and merit is the criterion for achievement." If that educational effort fails, McGill warned, victims of discrimination "may well be forced to deal with the matter in their own way." McGill's 1946 Siwasher article, "Not Utopia, But..." echoes the words of African Barnabus Root, Knox's first black graduate and first international student. Root wrote in 1868 that whites were prejudiced because they were "not accustomed to come in daily and familiar contact with the blacks." Through the 1940s, The Knox Student (TKS) editorialized against racial discrimination, asking "Do we practice what we preach?" While the context was discrimination in fraternity pledging, TKS noted the larger problem: "Not a single negro attends Knox at present."

When McGill returned to his community and campus after the war, he likely knew what he was coming to. Not so for William Hall '55, who came to Knox from Chicago in 1951. One of nine African American students on campus, Hall later recalled, "I was not prepared for the attitude of the town." He and white friends were refused service at a local lunch counter. When Hall pledged to join the Knox chapter of Phi Sigma Kappa (PSK) in 1952, the fraternity's national office and a number of alumni opposed the students, citing an unwritten rule against black membership. Hall later said he found himself described in PSK national publications as "the problem."

The College's response to PSK was unwavering support for the initiative taken by the students in the local chapter to admit Hall. The faculty withdrew the PSK charter because "the national fraternity's policy of racial discrimination has been invoked to thwart the voluntary course of action sought by members of the active chapter." The faculty said they would "sustain the right of any student organization to select its members without regard to race, color, or creed."

The College's response to PSK was unwavering support for the initiative taken by the students in the local chapter to admit Hall. The faculty withdrew the PSK charter because "the national fraternity's policy of racial discrimination has been invoked to thwart the voluntary course of action sought by members of the active chapter." The faculty said they would "sustain the right of any student organization to select its members without regard to race, color, or creed."

Most of the PSK chapter resigned in the spring of 1953, explained the Knox Alumnus, "because of the ‘intolerant attitude' of the national fraternity toward a Negro student pledged last year." Many of the former PSK members then created a new, independent local fraternity, Alpha Delta Epsilon (ADE). ADE was conceived in fall 1953 when, "one weekend, while on an out-of-town football trip, several Knox men formulated plans for a new and unique fraternity ... a fraternity with high ideals."

While student initiative was the spark, Knox was not caught unaware. Two years before Hall pledged PSK, President Sharvy Umbeck had appointed a committee to study discrimination in fraternity pledging. Later, a faculty resolution would prohibit discrimination in all student activities. Allied Blacks for Liberty and Equality (ABLE) was formed in May 1968, "in the wake of Dr. [Martin Luther] King's assassination," wrote Audrey Petty '90 in a 1999 Knox Alumnus article, a 30-year retrospective of ABLE. One of ABLE's first "suggestions and demands" in 1968 was for more black students and faculty. For a college that was founded by abolitionists on the ideal of racial equality, "we have an awful lot of catching up to do," said Ivan Harlan '52, dean of students, in an interview with TKS in November 1968. "In so many respects the requests of black students are appropriate. If some people think they are not, certainly they would have to understand why they are being presented. I think we would want to discuss such proposals and whether we're capable of carrying them out," Harlan said.

ABLE has continued to keep Knox focused on institutional commitments to diversity and equity. In April 1988, "nearly 20 years after [ABLE] mobilized to make demands on the College, a delegation of ABLE members interrupted a faculty meeting to present issues they believed required immediate response," Petty wrote. The issues included permanent space on campus for ABLE, which later developed into the ABLE Center for Black Culture, at 168 West Tompkins Street. The 1980s also saw the creation of an academic program, and eventually a major, in Black Studies; and increases in both black student enrollment and overall diversity. In fall 2011, Knox recorded a student body including 21 percent students of color, including seven percent African American, as well as nine black faculty and five trustees. "Knox's diversity along multiple dimensions distinguishes Knox from many other liberal arts colleges," said Lawrence Breitborde, dean of the college and vice president for academic affairs.

ABLE has continued to keep Knox focused on institutional commitments to diversity and equity. In April 1988, "nearly 20 years after [ABLE] mobilized to make demands on the College, a delegation of ABLE members interrupted a faculty meeting to present issues they believed required immediate response," Petty wrote. The issues included permanent space on campus for ABLE, which later developed into the ABLE Center for Black Culture, at 168 West Tompkins Street. The 1980s also saw the creation of an academic program, and eventually a major, in Black Studies; and increases in both black student enrollment and overall diversity. In fall 2011, Knox recorded a student body including 21 percent students of color, including seven percent African American, as well as nine black faculty and five trustees. "Knox's diversity along multiple dimensions distinguishes Knox from many other liberal arts colleges," said Lawrence Breitborde, dean of the college and vice president for academic affairs.

The dispute in 1868 between College President William Curtis and Female Seminary Principal Lydia Howard may have originated with a disagreement over the role of women in higher education, but the student strike that forced the ouster of Curtis was motivated by the president's behavior, as well as his policies -- students felt that Curtis had "insulted" Howard when he reportedly grabbed a document from her hand.

On a spring day in 1921, the Galesburg Evening Mail reported that Seymour Hall was the "scene of a near riot" by students who were upset that the administration was clamping down on campus hi-jinks. Overnight, pranksters had jammed the locks of Old Main with plaster, and later that day, the paper reported:

At lunch, Dean [William] Simonds announced that the men would be served only soup and crackers [and ham sandwiches] that evening, in order to make up the expenses of the damage caused to the locks of Old Main.... There was a spirit of discontent in the air.... Within a few moments, sour pickles, ham sandwiches and crackers were the ammunition of a pitched battle.... Serving tables were tipped over ... Then came the soul-searching: After the melee was over, there was much talk of a more or less bitter nature, regarding the actions of everybody concerned. Many of the students said that they could no longer be proud of such a school.

Some 50 years after the food fight, and 100 years after the Curtis "sit-down strike," another spring day saw another campus disturbance: the two-day "occupation" of Old Main in 1970. Unlike the pre-60s protests -- such as the aforementioned food fight -- this and other modern student protests/initiatives would have an intellectual dimension and regularly engage national and international issues. Arguably, the enduring linkage between campus and world politics was pioneered by the 1964 "Free Speech Movement" protests at the University of California-Berkeley. As stated on a monument to the movement, the protests came "at a time of passionate student involvement in civil rights demonstrations." Thanks to national media coverage, the Berkeley protests "resonated on campuses throughout the United States, inspiring student struggles for social justice and against the Vietnam War."

Some 50 years after the food fight, and 100 years after the Curtis "sit-down strike," another spring day saw another campus disturbance: the two-day "occupation" of Old Main in 1970. Unlike the pre-60s protests -- such as the aforementioned food fight -- this and other modern student protests/initiatives would have an intellectual dimension and regularly engage national and international issues. Arguably, the enduring linkage between campus and world politics was pioneered by the 1964 "Free Speech Movement" protests at the University of California-Berkeley. As stated on a monument to the movement, the protests came "at a time of passionate student involvement in civil rights demonstrations." Thanks to national media coverage, the Berkeley protests "resonated on campuses throughout the United States, inspiring student struggles for social justice and against the Vietnam War."

The occupation of Old Main for one weekend in May 1970 was undertaken by a small group -- between 15 and 30 -- who adopted the label "The Students Are Revolting." It was not the largest or the most visible Knox campus protest of the late '60s-early '70s, but it offers an iconic blend of Knox-specific complaints, such as a "repressive [campus] judicial process," with national concerns: "war in Asia, racism and poverty at home, repression and violence that has killed innocent people from Cambodia to Kent [State University], from Georgia to Vietnam."

Grades, classes, capitalism, careers -- all these were targets for the occupiers, who claimed the label of "countercultural." They argued that the faculty "continues to think that lecturing and exchanging views is enough." Some advocated cancelling classes or allowing students to take "incompletes" for the rest of spring term. But the vast majority of students signed a petition opposing any cessation of classes.

The position adopted by Knox faculty toward both the occupiers and their concerns proved to be "enough" -- flexible, yet not flimsy. Even prior to the occupation, faculty had been offering non-traditional "group interest" courses, including in 1969, "Non-Violent Direct Action," as well as "Readings in Conservatism." Following the occupation, Knox created informal academic programs, dubbed the "Experimental College" and "Satellite Curriculum." While faculty did not abandon the traditional curriculum of classes, labs, lectures, or grades, they participated in campus-wide discussions on the Vietnam War and other issues of concern to students.

One of those concerns -- student role in college governance -- had actually been raised two years earlier. Before they were the "Revolting Students," some of the same group created the Coalition of Concerned Students. They put forth "proposals," including, first on their list, "that students be given membership on all committees pertaining to student life." Knox faculty would do that and more -- students would eventually be seated on all but faculty personnel committees.

Finally, Knox faculty in 1970 rejected calls to do what other colleges often did in reaction to sit-ins: summon police and forcibly evict the protesters. That also proved to be the right response. While some on campus had worried about the possibility of vandalism to offices in Old Main, faculty and administrators met with and talked with the students, and the students left Old Main with no damage of record -- certainly less than did their prankster predecessors from "the good ol' days" 50 years earlier.

One of the courses in the short-lived Satellite Curriculum of the 1970s -- "Ecology Action" -- hints at an ongoing student interest that would coalesce through the '70s and '80s with the creation in 1989 of the student group KARES, Knox Advocates for Recycling and Environmental Support. "This campus is extremely behind other colleges in recycling," KARES asserted in 1991. The KARES agenda included elimination of plastic foam containers in the cafeteria and promotion of "recycling in every suite on campus." Students said they had "developed a campus-wide plan for paper recycling, which has been repeatedly stalled by the administration."

KARES had proposed in 1991 "making paper pick-up [for recycling] a work-study job for students," and with not surprising enthusiasm, the students proclaimed that "if [recycling] becomes a reality it will be a tremendous victory due solely to our lobbying efforts." The work-study positions were created in 1996. While KARES provided the impetus, the program required administrative structure and stability to keep it going smoothly. Since 2001, the positions have been supervised by Facilities Services, which also furnishes the students with a John Deere Gator and trailer to haul recyclables.

Student interest in all things environmental continued to build. The first environmental studies courses were offered in 1991, then an interdisciplinary program in the mid-1990s, a concentration in 1998, and a major by 2000. The number of majors exploded from seven in 2000 to 16 the next year, and more than 30 by 2008. Eco House at 675 S. West Street became a permanent residential and activity center in 2006 -- one of several "special interest" houses created at Knox in recent years. In addition to the aforementioned composting measure, the house also promoted water conservation by taking shorter showers and adopting the adage "if it's yellow, let it mellow" -- another endeavor that doesn't always smell or look the best.

An alternative to the traditional pattern -- student demand followed by administrative response -- is the President's Task Force on Sustainability. Created by President Emeritus Roger Taylor '63 in 2008, the task force ensures that sustainability will always be on the College's agenda, for both discussion and action. "Without the Task Force, there would be no ... sustainability faculty workshop, no EquiKnox speakers, no food clamshells" that replaced plastic foam take-out containers in the cafeteria, said Peter Schwartzman, associate professor and chair of environmental studies in a 2010 TKS interview. "It's essential to realize that students play an important role.... They have the passion and the open-mindedness."

The Knox College Catalog's condensed history of the Honor System is that it "was established by student initiative in 1951." For several years, students had known there was a problem. The Knox Student editorialized in 1950 that the College suffered from "a confusion of values which led the student body to accept, and in effect sanction the dishonest practices which have characterized ‘study' methods at Knox."

Faculty members were already on record with concerns about cheating. Spanish professor Lawrence Poston wrote to TKS in 1947 to discuss "the proposed honor system." In March 1949, the editors offered a remedy -- that "teachers [should] exercise more care in giving examinations ... make it impossible for students to cheat!" But Poston had questioned the effectiveness of a top-down approach: "To what extent would students ... comply with a superimposed honor system?"

The disease and search for a cure continued apace. In March 1950, TKS reported, six students were suspended "following an investigation that disclosed that they had cheated on a Spanish achievement test." The newspaper combined praise and lamentation:

We commend the administrative committee for its judicious action.... The promptness, intelligence and discretion [were] praiseworthy. We regret only that it was the administration and not the students themselves that openly recognized the seriousness of the problem of cheating and did something about eliminating the practice. We regret that positive action was not taken earlier by the students when they must have felt the graveness, the magnitude to which the problem had grown.

The student plan was in the works. In 1949, Student Council members Glenn LeFevre '50 and Ismat Kittani '51 attended a National Student Association conference at the University of Illinois and, TKS reported, "brought the suggestion [for an honor system] back to the Student Council." Following the Spanish test scandal, LeFevre wrote that "this is a student problem and should lie within the jurisdiction of our student government."

A group led by LeFevre and Kittani, who would later serve as the first Honor Board chairman, made its proposal in time for approval by the end of May 1950. Knox's Honor System, TKS wrote, would be "enforced by a student honor board ... three seniors, three juniors, and two sophomores ...This system, completely new to the college, will place the main responsibility for cheating and resultant disciplinary measures in the hands of the Knox student body."

A group led by LeFevre and Kittani, who would later serve as the first Honor Board chairman, made its proposal in time for approval by the end of May 1950. Knox's Honor System, TKS wrote, would be "enforced by a student honor board ... three seniors, three juniors, and two sophomores ...This system, completely new to the college, will place the main responsibility for cheating and resultant disciplinary measures in the hands of the Knox student body."

"The system will be completely administered by the students themselves," LeFevre told TKS. "The faculty has in no way been involved in the planning or establishment of the new plan." The Honor System created by the students rejected the enhanced enforcement that TKS had earlier advocated -- "make it impossible to cheat!" -- thereby avoiding the pitfalls of a "superimposed honor system" that Professor Poston had warned about.

Student initiatives do not emerge from some hyperborean reservoir of student idealism, and they do not always meet with institutional resistance. They also do not persist unchanged. In 1962, well after the system was created, a student wrote a forceful, detailed letter to the Honor Board: "The Honor System should be explained to every Knox student ... Violations should be made more detailed and explicit.... [The] spirit of the law should be developed." Several aspects of the current Honor System directly address the student's critique. Students and faculty now receive orientation sessions and a brochure that details violations and enforcement, greatly expanding on the original text of the Honor Board's 1950 Constitution. In 2011, the spirit of the Honor Code was brought to life in a new video that links the system not to past cheating scandals but to Knox's "core value of academic integrity."

Another significant change is increased faculty participation. Initially made up of only eight students, the Honor Board seated one faculty member starting in 1968, and now has two faculty members and nine students. The Honor Code Review Committee, which began in 2011 to study the effectiveness of the Code and propose changes, has equal representation of faculty and students.

If anything distinguishes Knox "student initiatives" and the College's response, it is that the best of them moved beyond complaining to communication, beyond apathy or acquiescence to active alliances. Faculty members now serve on the Honor Board, students on faculty committees. One could argue that without KARES, the College might not have gotten into recycling or composting as quickly as it did, and, without College support, recycling and composting might not have attained their current size or stability. Student initiatives, even the untidy ones, challenge the College to examine itself, to justify its inherited traditions to the current generation, and to evolve.

Equally important, the response of the College faculty and administration, shown in the historic record, is mature and democratic, said Lance Factor, George Appleton Lawrence Distinguished Service Professor of Philosophy, who is currently working on a history of the College. "Knox has a culture of understanding that says we have rules, but the rules also can be challenged," Factor says. "When student initiatives have occurred, Knox's response is to validate them, to create spaces on campus, in the curriculum, where students can do things, try things. This is something of which Knox can be proud."

GI Bill® is a registered trademark of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). More information about education benefits offered by VA is available at the official U.S. government Web site at https://www.benefits.va.gov/

1968

A.B.L.E. (Allied Blacks for Liberty & Equality) was founded.

Open to students of all races, uniting them around common concerns regarding the Black experience